Is Large Format still viable for Food Photography in 2019?

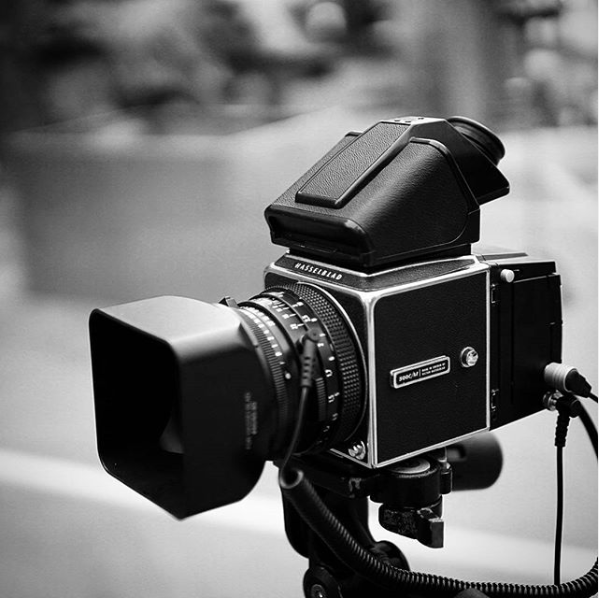

I have been a huge proponent of the largest sensor since I started shooting on a Nikon D70 in 2006. A larger sensor was always the solution. Lower Noise, larger photo sites, higher dynamic range, better bokeh etc. And soon enough I had found myself a Hasselblad 500cm.

The Prelude

The year was 2009 and the Hasselblad 500cm was a wonderful camera, it stood sholder to sholder with the medium format digtal bodies of the time, eg. hasselblad H3D-31, etc. I would chuckle that I was saving myself heaps of money while still getting a larger “sensor” with heaps more dynamic range on negative film.

I took this camera on quite a number of holidays, Tasmania, Italy, Hong Kong, etc. it was a bit heavy, but it was the perfect companion for landscapes where you had all the time in the world to compose, expose and focus before deciding that the scene was not worth the cost of film.

I took this camera on quite a number of holidays, Tasmania, Italy, Hong Kong, etc. it was a bit heavy, but it was the perfect companion for landscapes where you had all the time in the world to compose, expose and focus before deciding that the scene was not worth the cost of film.

By now, you would have noticed that the Hasselblad 500cm is not large format, infact far from. The Hasseblad 500cm was what got me interested to venturing into the unknown.

After many unsuccessful bids on eBay, I was delighted that Andrew from Cathay Photo found me a used Phase One P45+ with “only” 200,000 actuations. I gladly picked it up on the spot, that was the final moment before I slid down the slippery slope to heavy gear and many encumbrances.

Some years before picking up the P45+, I was lucky to have seen an ad for a Sinar P with a Schneider Super Angulon 90mm f/8 by Jimmy Fok (see Jimmy’s beautiful portfolio).

Fast forward many years to 2017, I found the sliding back to piece everything together, so that my Phase One P45+ would mount on the Sinar P correctly so I could use it for work. I had a glorious choice of the 90mm f/8 for wide shots, and a Rodenstock 150mm f/5.6 for close ups. I would have much preferred a Nikkor Micro 150mm but those are pretty rare, even on eBay.

Is Large Format better?

For a food photography studio like ours, such large and heavy camera does come with its unique set of problems.

Here are some issues to consider.

- Everything is in reverse – There is no mirror or prism on the Sinar, so when you look through the ground glass to compose, up is down, left is right. Unlike the Hasselblad where only left and right are switched. If you can’t deal with this, you can get a prism viewfinder, and get the camera to feel and compose like a SLR.

- Large cameras require large support equipment – the usual Manfrotto 055 was not ready for this behemoth of a camera, we upgraded to a 455 with a 029 panhead, and that too did not work well. It finally settled down on a Manfrotto Salon stand I was fortunate to come across used.

- Slow. No, really slow – I remember when we started using the medium format Hasselblad 500cm commercially, that it made the shooting process much slower. We had to prefocus, compose, then focus again before waking the back, re-cocking the shutter then firing off a shot for sure. Because there was no TTL or autofocus, everything had to be manually adjusted to get a useable image. This was acceptable for food photography because our subjects did not move much and we had all the time in the world to get all the micro adjustments dialled in. Compared to a Nikon DSLR tethered, the Hasselblad was 3-5 times slower.Now, with the Sinar, this was a whole new ballpark, not only was it heavier, and had more fiddly parts than the Hasselblad, we needed a whole new process because there was no mirror, and no auto diaphragm. you do notice that as these cameras get older, less and less of the camera is automated, requiring an experienced operator to get the most basic of images.

The process went something like this, you first had to open the shutter in the lens and the diaphragm so you could see what was infront of the camera, followed by the usual prefocus, compose then fine focusing, then is is where most photographers get lost. You need to remember to close the shutter, stop down the aperture, slide over the digital back so it can capture an image, wake the back, re-cock the lens shutter, then cross your fingers that you did not forget a step. This was maybe 5 times slower than if you did this on a medium format setup like the Hasselblad, and probably 10 to 15 times slower than a DSLR on a good day.

- Changing lenses are a huge hassle – The Sinar is made up of many removable and interchangeable parts, you can practically slap on any large format lens regardless of brand or era since everything, including the shutter and aperture blades are independent of the lens. The bad thing is, because everything is interchangeable, everything needs to be locked and tightened down extra tight to prevent components from falling out. We really only shoot with 2 lenses when we shoot with a DSLR have a look at our lens choices here.

- Not enough learning materials online – If you are new to this, it is a huge uphill learning curve to get the camera to operate right. There are just too many variants and too little users to get easy instructions online. We are seriously considering a training series online to help our junior photographers in the studio understand the system better.

- Firewire – Especially for us, using an older system that only accepts Firewire connection for tethering, it is starting to become a real nuisance getting right hardware for digital back to run.

Examples

Here are some images taken using the P45+ on either the Hasselblad or the Sinar

Now for the good!

Now that we have done with all the bad, here’s some good.

- 16 Bit RAW – For us, this is the #1 reason we would go through all the trouble, the P45+ is by no measure a young sensor, and even with age quickly catching up, it brings stunning results every time, even compared with newer, higher megapixel DSLR sensors. The difference is most apparent in the way colours are rendered on the larger sensor, and we have found no way to replicated this on a DSLR.

- Tilt and Shift – After the iPhone introduced the faux tilt shift function in the camera app, tilt and shifts have become a huge photographic faux-pas, with many professionals avoiding the topic all together in a hope to define their chosen profession. For us food photographers, shift, and especially tilt have come in very useful time and time again. There are many modes of digital trickery, like stacking and compositing that have help alleviate the need for tilt, but there are many a times that we have found it unavoidable, especially when subjects get close and where it becomes a challenge to get enough depth of field.

Conclusion

With the expectation of haste and convenience in today’s market, it might be a reality that less and less photographers can accept older, slower formats in place of small, light and powerful newcomers like the Nikon Z system and the Fuji GFX range of medium format cameras.

From a studio point of view, we will continue shooting billboard advertising with these amazing cameras for as long as they remain creatively competitive, for now, that means as long as we are in the studio, it is going to be a Sinar or Hasselblad at work, but if we are leaving the studio, then its likely to be a DSLR or even a mirrorless body. What are your thoughts?